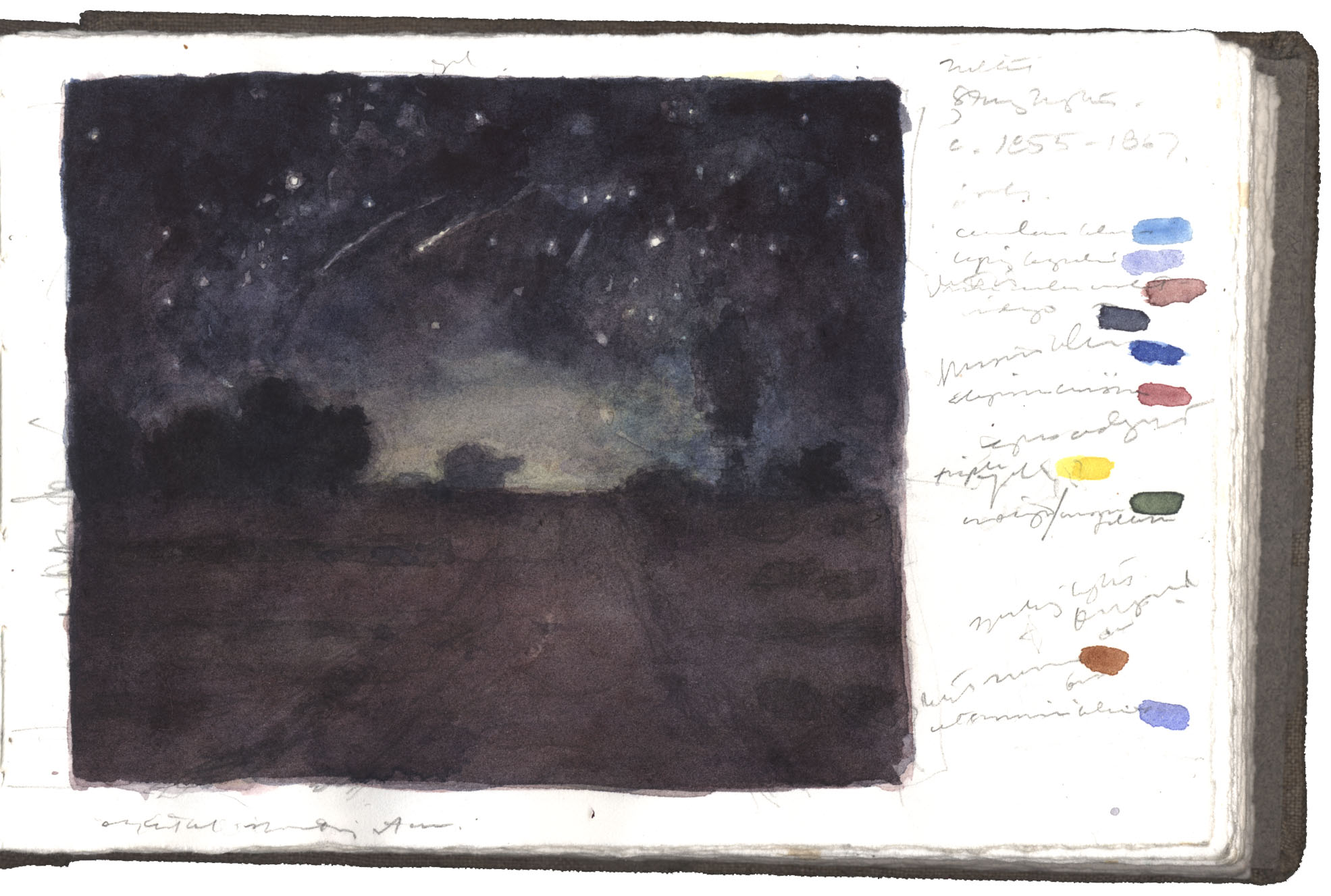

Charles Ritchie, Study after Starry Night by Jean-François Millet, 27 April 2008, watercolor and graphite on Arches paper in bound volume, sheet size: 4 x 6″

Millet’s Falling Star

The Painting:

What a thrill to finally see Jean-François Millet’s painting Starry Night. I had known it previously only through a poor black and white reproduction. When I discovered the work hanging with the In the Forest of Fontainebleau exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, I was stunned to see its boiling darkness.

But the more I looked at the subject the more something seemed out of place. In Millet’s picture, we stand in a dark road with fields on either side. Trees are silhouetted against a glowing horizon that bleeds upward into a dark sky of accurately observed constellations. To the right, the belt and sword Orion are prominent and Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky follows at upper left. What troubled me is that another star stands just to the right of Orion’s belt, challenging Sirius. No bright star is in this location nor do bright planets tread there. What a terrible inaccuracy for Millet, an artist who prides himself on truth to observation.

In the left center are two streaks of falling stars; one with a fiery head and another, a vaporous streak. It suddenly became clear to me, that by reading a right to left sequence, we see three stages of a single falling star: the bright flash of the meteor’s encounter with earth’s atmosphere (the misplaced star in question), the flaming rock’s descent (at center), and the vaporized trail still illuminated (at left). When we consider the image this way; the metaphor is clarified; individuals are no more than a single falling star in the night. The dark road where we stand is transient and solitary.

Copying Technique:

To make my copy I stood in front of the actual painting penciling out the composition in my journal and recording an inventory of the colors I saw. Returning to the studio I painted the image in watercolor based on my notes and a reproduction that I printed from the Yale University Art Gallery web site; an image that carried far more detail than any catalogue reproduction I could find. I began my watercolor with light application of three loosely blended yellows: Winsor, Indian, and Naples, the three give a warm underpainting for the stars and the glowing horizon. I then begin to work with darker colors moving from light to dark, never wetting the pinpoints where the stars are located. This allows the white of the paper to spark through in these areas. Other colors I used in the general order I introduced them: Cerulean Blue, Lapis Lazuli, Burnt Sienna, Ultramarine Blue, Winsor Yellow/Indigo (a color that I mix to get a transparent, versatile green), Alizarin Crimson, Prussian Blue, Raw Umber Violet, and Indigo. By the way, one should take this color study with a grain of salt. Millet’s painting needs to be cleaned. Who knows what will emerge when the old varnish is stripped away.

Other Notes:

It is not known for certain whether Van Gogh saw Millet’s painting before he painted his well-known masterpiece. Millet prefigured; he was a force from earlier in the 19th century and his works influenced Vincent. Both shared an interest in rendering subjects from everyday life with deep compassion.

Serendipity placed this painting in my path considering I’ve been involved with my current, unfinished Night with Orion drawing. I admit the influence of Millet’s painting on me, however, I don’t remember being conscious that Orion and Canis Major (Sirius is the prominent star of the latter constellation) were part of Millet’s Starry Night.

Much credit goes to the wonderful article, Millet’s Shooting Stars by Martin Beech, Royal Astronomical Society, Canada, 1988. Beech’s insightful study fueled some of my questioning. Beech, however suggests that these are several meteors belonging to the Orionids, an October shower emanating from the Orion region of the sky (actually the radiant is well above the core of Orion, see here). I believe that because Orion is leaning to the right in Millet’s Starry Night, the constellation is falling into the sunset (as it does in the mid-Northern latitudes). With plenty of foliage visible, I would say this is late spring when Orion sets just after the sun.

Charles Ritchie, Study after Starry Night by Jean-François Millet (first state), 24 April 2008, watercolor and graphite on Arches paper in bound volume, sheet size: 4 x 6″

Link to Jean-François Millet (French, 1814–1875), Starry Night (Nuit Étoilée), c. 1855-1867, oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 32″, Yale University Art Gallery.